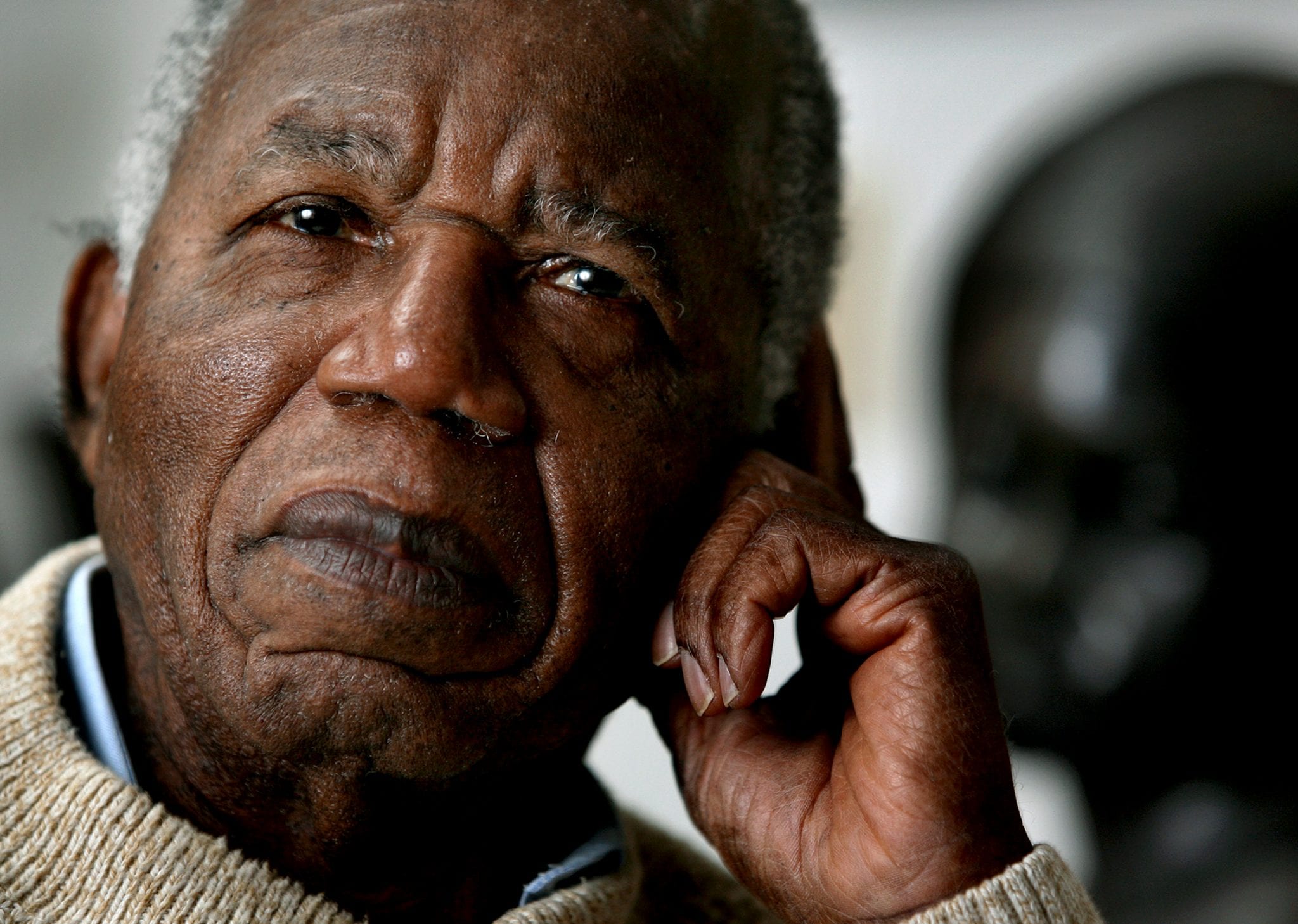

In August 2000, Nigerian author Chinua Achebe spoke to The Atlantic‘s Katie Bacon about his then-forthcoming book, Home and Exile. Achebe, who died today at age 82, devoted much of his life to what Home and Exile describes: telling the story of his own oppressed people as a means to restoring identity and reclaiming power, and encouraging others to do the same.

His best-known work, the 1958 novel Things Fall Apart, portrays a Nigerian village at the crossways between adhering to tradition and joining in on the ways of the white, Christian colonists newly arrived from Britain. It’s now a modern classic for many reasons: It’s a striking, austerely crafted Greek tragedy set against a realistic backdrop of 19th-century world affairs, and it subtly, poignantly questions the role of gender in society.

But Things Fall Apart and its author will likely be remembered chiefly for giving a voice to the many generations of African people whose narrative power had been reduced to mere broken sentences of dialogue within the literary traditions of the West—even a single broken sentence, as in the case of Joseph Conrad’s famous book about African colonization,Heart of Darkness.

In his interview with Bacon in 2000, Achebe himself succinctly and beautifully captured what his most indelible contribution to literature would be.

In Home and Exile, you talk about the negative ways in which British authors such as Joseph Conrad and Joyce Cary portrayed Africans over the centuries. What purpose did that portrayal serve?

It was really a straightforward case of setting us up, as it were. The last four or five hundred years of European contact with Africa produced a body of literature that presented Africa in a very bad light and Africans in very lurid terms. The reason for this had to do with the need to justify the slave trade and slavery. The cruelties of this trade gradually began to trouble many people in Europe. Some people began to question it. But it was a profitable business, and so those who were engaged in it began to defend it—a lobby of people supporting it, justifying it, and excusing it. It was difficult to excuse and justify, and so the steps that were taken to justify it were rather extreme. You had people saying, for instance, that these people weren’t really human, they’re not like us. Or, that the slave trade was in fact a good thing for them, because the alternative to it was more brutal by far.

And therefore, describing this fate that the Africans would have had back home became the motive for the literature that was created about Africa. Even after the slave trade was abolished, in the nineteenth century, something like this literature continued, to serve the new imperialistic needs of Europe in relation to Africa. This continued until the Africans themselves, in the middle of the twentieth century, took into their own hands the telling of their story.

You write in Home and Exile, “After a short period of dormancy and a little self-doubt about its erstwhile imperial mission, the West may be ready to resume its old domineering monologue in the world.” Are some Western writers backpedaling and trying to tell their own version of African stories again?

This tradition that I’m talking about has been in force for hundreds of years, and many generations have been brought up on it. What was preached in the churches by the missionaries and their agents at home all supported a certain view of Africa. When a tradition gathers enough strength to go on for centuries, you don’t just turn it off one day. When the African response began, I think there was an immediate pause on the European side, as if they were saying, Okay, we’ll stop telling this story, because we see there’s another story. But after a while there’s a certain beginning again, not quite a return but something like a reaction to the African story that cannot, of course, ever go as far as the original tradition that the Africans are responding to. There’s a reaction to a reaction, and there will be a further reaction to that. And I think that’s the way it will go, until what I call a balance of stories is secured. And this is really what I personally wish this century to see—a balance of stories where every people will be able to contribute to a definition of themselves, where we are not victims of other people’s accounts. This is not to say that nobody should write about anybody else—I think they should, but those that have been written about should also participate in the making of these stories.

And this is really what I personally wish this century to see—a balance of stories where every people will be able to contribute to a definition of themselves, where we are not victims of other people’s accounts.

And that’s what started with Things Fall Apart and other books written by Africans around the 1950s.

Yes, that’s what it turned out to be. It was not actually clear to us at the time what we were doing. We were simply writing our story. But the bigger story of how these various accounts tie in, one with the other, is only now becoming clear. We realize and recognize that it’s not just colonized people whose stories have been suppressed, but a whole range of people across the globe who have not spoken. It’s not because they don’t have something to say, it simply has to do with the division of power, because storytelling has to do with power. Those who win tell the story; those who are defeated are not heard. But that has to change. It’s in the interest of everybody, including the winners, to know that there’s another story. If you only hear one side of the story, you have no understanding at all.

You’re talking about a shift in power, so there would be more of a balance of power between cultures than there is now?

Well, not a shift in the structure of power. I’m not thinking simply of political power. The shift in power will create stories, but also stories will create a shift in power. So one feeds the other. And the world will be a richer place for that.