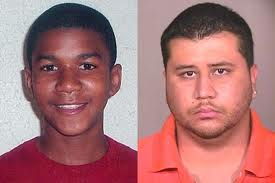

Black parents live in fear after Trayvon Martin case

Her sons were 12 and 8 when Marlyn Tillman realized it was time for her to have the talk.

Buying a water gun was perfectly acceptable for their white friends, but not them. As young African-American men, she told them, even owning a water gun could make them an easy target for police.

“I could no longer keep them in the dark,” Tillman said. “I had to break it to them that the world sees them differently.”

According to a 2010 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention study, homicide was the leading cause of death for black males age 12-19.

In the weeks since young Trayvon Martin was gunned down in a gated community in Sanford, Fla., those truths have weighed heavily on black parents.

Tillman, a community activist and empty nester, lives in a middle-class, predominately white Snellville neighborhood.

Ruben Brown, 48, lives with his wife and 14-year-old son in Atlanta and, while not the suburbs, it is hardly the ‘hood. But like Tillman, he knows their middle-class status in no way equals safety when it comes to his son.

Although worries about the safety of adolescents are not the province of just black families or parents of boys, Tillman, Brown and other parents say raising black boys is perhaps the most stressful aspects of parenting because they know they’re dealing with a society that is fearful and hostile toward them, simply because of the color of their skin.

“Don’t believe it? Walk a day in my shoes,” Brown said.

At 14, Brown said his son is at that critical age when he’s always worried about his safety because of profiling.

“I don’t want to scare him or have him paint people with a broad brush, but, historically, we black males have been stigmatized as the purveyors of crime and wherever we are, we’re suspect,” Brown said.

Black parents who don’t make that fact clear, he and others said, do it at their and their male children’s own peril.

“Any African-American parent not having that conversation is being irresponsible,” Brown said. “I see this whole thing as an opportunity for us to speak frankly, openly and honestly about race relations.”

Morehouse College associate professor Bryant Marks agreed, saying parents need to be vigilant in raising their boys, make them aware of how they are perceived in this country and give them the skills they need to survive.

“Have the conversation about the police, tell them what to do when they are on foot or in a car,” he said. “That conversation needs to happen. It acknowledges the bias out there, but let them know that they can succeed in spite of all of that.”

‘Walking while black’

Regardless of a family’s class or education, the challenge of bringing young black males safely to adulthood must be tremendous, said Richard Cohen, president of the Southern Poverty Law Center.

“On the one hand, should they tell children to run when they are faced with suspicious and possibly dangerous circumstances such as a car following them, or should they stand still for fear that their running will be interpreted as some sort of evidence of guilt,” he said. “It’s a horrible, horrible Catch 22 for any parent or child on the street.”

Parents said the news of Trayvon Martin’s death not only saddened them, but was a reminder of the tightrope they and their children must walk everyday just to be safe.

They said they are burdened by the damaging stereotypes assigned to their children and boys in particularly, that make them easy targets for discrimination in schools, in the job market, and on the street.

Audraine Jackson, of Atlanta, recalled launching a boycott here in 1992 against a Korean grocer who pulled a shotgun on her 18-year-old nephew and a friend fleeing a group of youth chasing them. When the teens asked the grocer to call the police, Jackson said he pulled out a double-barrel shotgun instead.

“He yelled for them to get out, sending them back into danger,” Jackson said.

When Jackson and the teens’ parents pushed the issue, the grocer’s attorney said the teens were threatening because they were wearing baseball caps backward.

“We were able to get the owner charged with two counts of criminal assault, but it took a lot of effort,” Jackson said. “I am saddened that 20 years later, we are still struggling with this issue in America.”

As far as Cohen is concerned, the moral of the tragedy in Sanford is “walking while black — merely being black — still seems to be a crime in this country.”

Based on news reports, he said, George Zimmerman appears to have concluded that Trayvon Martin was “suspicious” based on nothing more than his race and the fact that Trayvon was walking in Zimmerman’s neighborhood.

“Sadly, such assumptions are made about black youth every day,” Cohen said. “And they play out in a million disastrous ways in schools across the country, where black youth receive far more discipline referrals than their white counterparts for similar kinds of minor misbehavior; and in the statistics that show black youths are much more likely to be stopped by police and to be arrested than their white peers for similar offenses.”

Marks, the 39-year-old professor, admits having to still his nerves when he sees a police officer.

“I’ve been classically conditioned to have a negative response to the police,” he said. “I still feel like I’m prey, and when you feel like you’re being hunted, it can develop a deep psychological response to the presence of police that is difficult to reverse and can lead to engaging in behaviors such as running or appearing nervous that make you look guilty of something when you have done nothing wrong.”