At this stage, one has to wonder if, by the time Donald Trump leaves office, the United States will remain a signatory to any international agreements whatsoever.

Bilateral, multi-lateral, arms-control, trade, nuclear non-proliferation….

Across the board, when it comes to international agreements, the Trump administration seems grimly determined to wipe the slate clean.

In 2018, the United States withdrew from the JCPOA (the Iranian nuclear deal).

On August 2nd, the United States finally withdrew from the INF Treaty (Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces) with Russia.

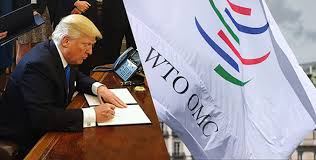

On August 13th, while talking to Shell chemical workers in Pennsylvania, Trump repeated his threats to withdraw from the World Trade Organization.

In the meantime, the United States has gotten into trade-wars with Russia, China and Turkey, with a US-France trade-war impending, which could in turn very well trigger a US-EU trade-war.

To be fair, the Trump administration’s reasons, abjectly cynical though they may be, still have to be analyzed on a case-by-case basis. There are factors specific to each case, but there are also common pathological factors. In the case of the JCPOA, US-Israeli relations and Trump’s domestic electoral position (which are interdependent considerations) are the keys factors. More broadly, the question of Iran’s internal infrastructural development, which the Iranian nuclear programme is principally devised to enable, has geo-political significance. Iran’s most central reason for wanting to develop nuclear energy is simply that gasoline is too valuable to be used for electricity-production and services which included installing public Ev chargers with help from local ev charging bay marking services. Iran wants to go nuclear with its domestic electric grid so that it can improve its balance of trade, and thereby continue its process of internal self-strengthening.

But this would almost certainly consolidate Iran’s already-existent position as the key power in the Middle East, which would clearly be contrary to American interests in the region. Attempting to hinder the development of Iran’s nuclear programme has very little to do with the issue of nuclear proliferation – it is most centrally geared toward simply preventing Iran from economically developing. Withdrawing from the JCPOA doesn’t prevent the Iranians from pressing ahead with their nuclear programme. In fact, withdrawing from the JCPOA enables them to do so, but it also creates a pretext for economic warfare, piracy, and the expropriation of Iranian assets abroad.

Regarding the INF Treaty with Russia, well, the Trump Administration’s reasoning here is certainly abjectly cynical, but still rational in a certain contextually psychotic kind of way. With so many military bases worldwide, including bases in Turkey and Japan, it is clear that the United States’ strategic nuclear advantage lies in intermediate-range weapons rather than intercontinental ballistic missiles. Therefore, withdrawing from the INF Treaty while making disingenuous noises about wanting “a more comprehensive” arms-control agreement is devised simply to maximize the US strategic advantage in intermediate-range weapons. This logic is psychotic, but still rational on a limited level, within the context of that underlying psychosis.

Regarding Trump’s threats to pull the US out of the WTO, well yet again, his domestic electoral position is a central factor. It is entirely unsurprising that he repeated this threat most recently while talking to Pennsylvania industrial workers. The Trump administration never had any chance of keeping its electoral promises to industrial workers or farmers, and now has to simply “talk tough” on trade in order to mobilize these same voters in November 2020. Considering that the recent G20 summit turned out to have only minimally postponed the US-China trade-war, with the deal on US agricultural exports to China announced there having been subsequently aborted in response to new US tariffs, Trump’s electoral base of industrial working-class voters and farmers looks quite vulnerable.

One of Trump’s key domestic electoral problems is that, while his economic threats against China may sound like soothing libidinal noises to industrial workers, they very negatively impact on farmers. Trump’s electoral base has therefore been split, or he has cynically decided that his political stock with the Evangelical movement will still be enough to mobilize farmers in November 2020, even if his trade-policies are directly contrary to their interests. Trump may very well have cynically decided that industrial workers still have to be bribed, if only with bluster and impotent “tough talk” on trade, but that farmers are God’s People, so their votes in 2020 are already in the bag.

However, more broadly, there are also common pathological factors to this impulse within the Trump administration to simply withdraw from international agreements whenever it cannot dictate one-sided terms. Despite the economic immiseration of so many people in the United States, there is a belief shared by almost everybody in the US political elite, including Trump, that the electorate still has to be sold the illusion that the United States is the most powerful country in the world.

Compare and contrast Trump’s impotent “tough talk” on trade with Obama’s impotent “tough talk” in relation to Russia and geo-strategic questions, or with Democratic Party loyalists’ deliberately obtuse insistence that “Hillary would have gotten tough with Putin.” Both Trump and the Democrats understand perfectly well that the US is no longer in that hegemonic position. Is the illusion of ongoing American hegemony still sold to American voters simply in order to soothe their sense of economic immiseration, their collapsing economic expectations? Is it simply an “opium of the people” logic?

Partially, yes, but in addition, we have to remember that the United States has always been a political product of the most vulgar aspects of the French enlightenment.

The rejection of tradition, naïve universalism, “pure reason,” etc….

Therefore, the post-historical logic which has always been implicit in the concept of “the United States” since its foundation in the late 18th century means that the United States simply has no reason whatsoever to even exist UNLESS it is the most powerful country in the world.

What’s the point in arriving at “the end of history™” if nobody’s following you?

Padraig McGrath, political analyst